Building Relationships For Life

Jay Norvell has a group which will back him always, some since he could first stand on his own

Mike Brohard

Jordon Simmons was on his couch, watching television with his father. The discussion was about whether or not Simmons was going to make the call.

He told his dad, Jerry, a two-decade veteran NFL strength and conditioning coach, he was going to give it a couple of days. Then his phone rang.

It was Jay Norvell.

————————————————————————————

When Colorado State’s coach turned 60 last summer, his wife Kim threw him a surprise birthday party, the room at Canvas Stadium filled with all of his nearby friends and family, even some who had traveled in from some distance. To fill the gap for those who could not attend, Kim put together a collection of videos all wishing her husband congratulations.

It was 19 minutes long.

The video compilation was a who’s who of NFL and college coaches and players, people Jay had touched through the years. In the middle was one made by Fred Hable. It wasn’t from his office or his living room, but he stood outside of the home where Jay had grown up as a child.

It was across the street from Orchard Ridge, where both Jay and Hable attended school together from kindergarten through eighth grade. Hable pointed out the Norvell home and all the places they used to play whatever game was in season, recalling how the local priest would run them off the field when the light started to fade. It was in kindergarten where Hable and Norvell first bonded, and to this day, they remain close friends.

It was the school where Rose Brown was hired to direct the new third-grade class. She was the only Black teacher at the school and her classroom had one Black student, Jay. Her husband worked at the University of Wisconsin with Jay’s father, Merritt. She became close with Jay’s mother, Cynthia, and the two couples grew close. And Rose, long after that third-grade year was over, kept a watchful eye over Jay.

Jay sees Jordon nearly every day of the year. He and Hable talk or text constantly, with Hable attending about five or six games per season. Brown sends him text messages often, and you can guarantee she’ll send him a note after every game.

Everybody has ride-or-dies in their lives, the friends they can count on through thick and thin, the conversations which don’t need to be every day but pick up where the last one trailed off. Some bonds are formed later in life, say in college. Others can date back to high school, but there are few friendships which stand the test of time from when someone was first learning to stand on their own.

Jay has multiple. And all of them will tell you it’s for the same reason.

“I think it’s his personality. He’s sincere. If he meets you and really tries to befriend you, he’ll stay in touch with you,” said Brown, who retired back home in Baton Rouge, where she recently celebrated her 87th birthday. “He grew up with some of these children in kindergarten, and my class was a marvelous class for him. He really stayed in touch with them.

“I think it’s just him being real with people that makes him stay in touch. In other words, I am up now, I’m not going to forget you.”

————————————————————————————

Jordon answered the call immediately.

He first met Jay when he was in the strength and conditioning department at Oklahoma. In those three years, he became enamored with the assistant coach, the way he spoke to people and looked them in the eye, the relationships he built with the players on the team and the coaches around him.

He knows they all had to feel it, the care and sincerity with which the man spoke. These weren’t conversations for the sake of taking up time in the hallway. When Jay spoke, his words conveyed care. When they spoke, he listened, intently.

Jordon left football and went to work for the military. Then he ran a business in Charlotte, N.C., which he liked. He was never sure he would get into football again, but when he heard the news Jay was hired at Nevada, he knew exactly the one man who he would return to serve.

“My phone rang, and I saw his name on my phone. Actually, his first words to me are an incredible indicator of who he is,” Jordon said. “I said hello, and he said, ‘hey Jordon, this is Jay Norvell.’ Yeah, I know. That’s just him. He’s a humble guy. Instead of him expecting me to know who it was, he introduced himself to me. He asked me what I was doing and if I was still doing the military job. He asked me what I was doing at the time, and I told him I owned a kickboxing gym. He asked me if I liked it, and I said I enjoy it. He asked if I wanted to get back into football, and I said, ‘yes sir.’

“He flew me out and I interviewed, and we caught up a bit. Then he grilled me. I got upset at my dad for that, because he said, ‘he called you, it will be fine.’ Coach asked me for my program, and he threw it in the trash and had me stand up and write up my program up on the whiteboard. He wanted to see if I knew it or if I had just typed something up. Then he took it out of the trash, checked it against the board and gave me the opportunity.”

Back in Oklahoma, Simmons knew: Jay was a man he would follow any time, any place.

————————————————————————————

You can call it charisma because Jay can fill a room. He can do it with his presence, but particularly with his smile and laugh. He will sit for days and tell stories, all the experiences which shaped him and in turn, those around him.

He talks often about his parents and how he was raised. How they impacted others, and he learned as much from watching their interactions as he did heeding their words. There is a picture of Merritt and Cynthia on one of his office tables, and in between them stands Muhammed Ali. Every recruit who enters the space is going to hear the story about the perfectly framed shot.

“It was in the late 60s when Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X and Muhamad Ali were traveling around college campuses speaking, and my dad used to set that up,” Jay led in. “They had a reception for Muhammed Ali, and that picture is at the reception. My mom was very attractive; she was a model. So, Muhammed Ali saw my mom and walked over and started talking to her. My dad was across the room and saw this, so he gets up and goes over there and Muhammed Ali looks at him and says who are you? My dad says, ‘I’m the guy you’re going to knock out tonight because that’s my wife you’re talking to.’ Right then, they took that picture. I love that picture because they just laughed.”

It’s unique, that’s for sure. I’ve known Jay longer than some of my brothers and sisters.Fred Hable

The best stories – lessons really – stem from the house across from the school.

The Norvell house was the epicenter of the neighborhood. It was the starting point for the day and quite often the ending point. Jay is that house – welcoming, accepting and always open.

“Jay’s parents, that’s a great place to start,” Hable said. “They were wonderful for us. And their home was centrally located, across from the school, next to the church and the pool was over the hill. Because of them – mostly because of them – it was a hangout place for us. We’d shoot baskets or something was going on there. That was definitely a calling card for us, the Norvell homestead.

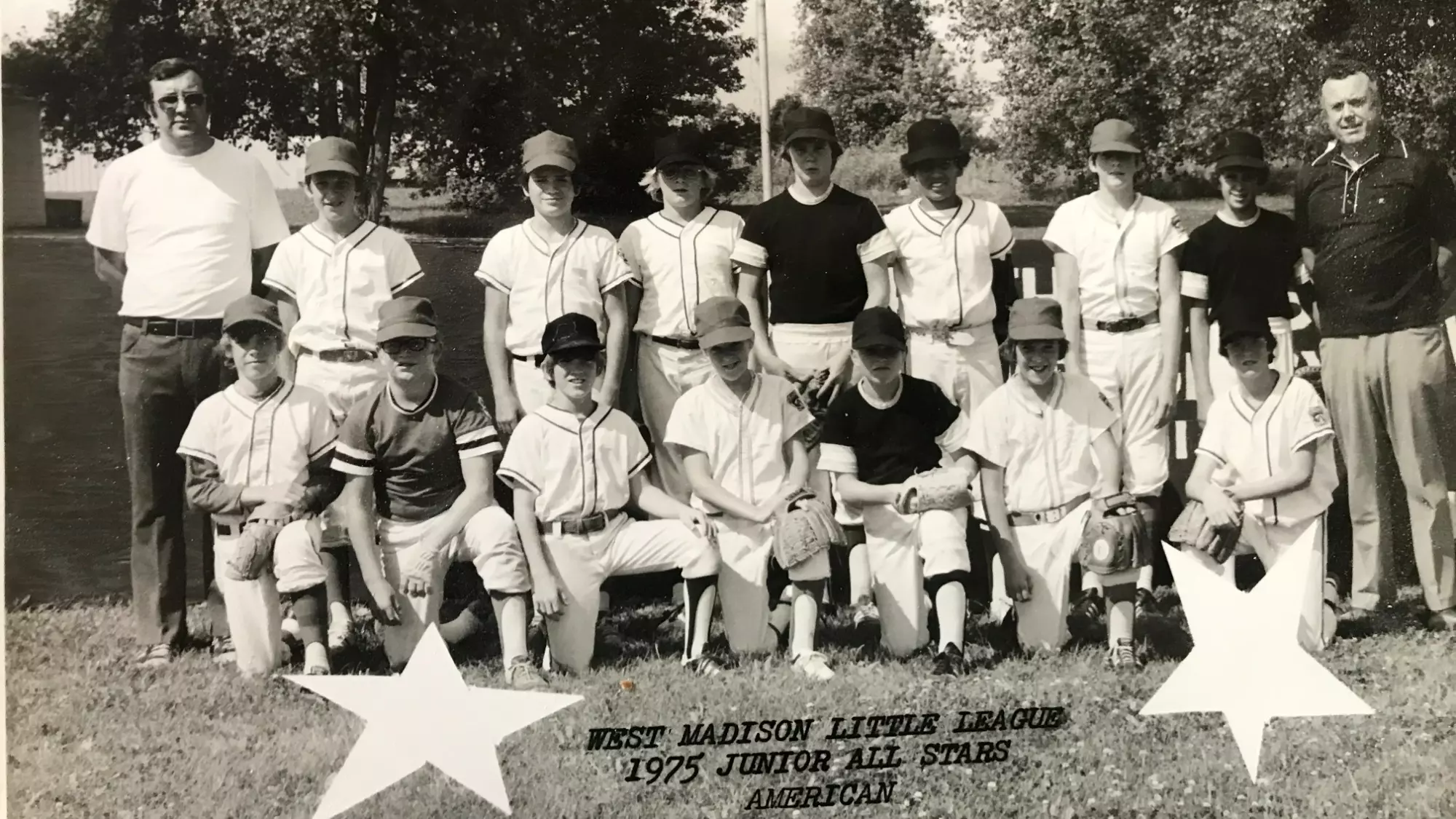

“They were not just the neighborhood, they were community wide. They were active at the University of Wisconsin, and that was Merritt and Cynthia. A Little League game or a high school game … They were involved in Special Olympics. I truly credit that to Jay’s ability to adapt. He was that person in high school. He had friends of all groups.”

Merritt and Cynthia taught Jay the meaning of community with their actions as much as their words.

He cherishes the fact of when and where he grew up, during the 60s and 70s in Madison, Wisc. The midwestern values, the way the neighborhood looked out for each other. Those were the days when a kid jumped on their bike after breakfast and returned when the street lights came on. Nobody had cell phones and not a single parent worried. Eyes were always watching.

“If you did something wrong, my neighbor’s mom would come over and tell my mom, this Norvell boy did this,” Jay said with a laugh. “There was a sense of community. Our neighborhood team, we wanted to beat the other neighborhood team. And we didn’t need adults around. That’s the way we grew up.

“Community is really important to me. Fort Collins reminds me a lot of Madison, a lot of Midwest values and people value their neighbors here.”

————————————————————————————

The memories, those are the best. They played everything when it was in season. They jumped from football to basketball to baseball. Growing up, they made up games. Tenny ball, they called it, using the three-story wall at the school as a replica of the Green Monster. Hable said they took turns hitting left handed so they could hit it, picturing themselves as Jim Rice, Fred Lynn or Carlton Fisk, the Boston stars of the time. Heck, Jay was even a really good hockey player, giving it up when he moved to high school.

“That was fun. Such fond memories,” Hable said. “We played whatever sport was the season. Then for football we’d go on the church lawn and play. If it was basketball season, we were playing basketball.

“It’s unique, that’s for sure. I’ve known Jay longer than some of my brothers and sisters.”

They stood up at each other’s weddings. They were in attendance for parent’s funerals. Every year, Fred and his wife, Renee, vacation with Jay and Kim. This past February, they went to New York City and saw some shows on Broadway and took in much of what the metropolis has to offer.

And every Fourth of July weekend, Jay returns to Madison.

One of Jay’s favorite fun facts is when he was a star pitcher growing up, he only had two catchers. Hable was one, Kent Fitch was the other. When Jay threw out the first pitch at a Rockies game, he asked the team if Hable could catch for him, but the plan never took hold.

“Kent Fitch, he was another lifelong friend. About four or five years ago, he had MS and he passed away,” Jay said. “Every summer we’d all play golf and have this Fourth of July party in his name. In Wisconsin, they have this huge summer festival called Summerfest. It’s awesome. It used to be like 10 days, and basically, you’d go to the lake front in Milwaukee and have like 30 or 40 bands. Rock and roll, country western, hard rock, blues, and then they’d have a main stage. I’ve seen Prince there, all the big 70s and 80s groups, REO Speedwagon and Journey, Morris Day and the Time. Anybody you ever listened to on the radio played there.

“We’d go there every summer, and when Kent got MS and it became hard for him to go, we started doing this Fourth of July party. It’s in his honor, so that same group of friends, we’re still very connected.”

The party is so big, Hable’s wife thinks they’re all nuts. It can reach up to 50 people on the Fourth, most of them lifelong friends and families, but the core friend group stays tight and gets in a round of golf or two. This year, Jay saw his middle school basketball coach for the first time in years. He showed up and caught up over a beer and a brat.

When the night gets dark, they set off fireworks. No more fighting the crowds to go to the show the city puts on, no sir.

“We still do old school. We have our own fireworks,” Jay said. “We don’t go see the city. We have a blacktop, and we shoot fireworks off and the whole neighborhood out there. It’s awesome.

“I still have a core of friends I’ve known my whole life. I have guys coming to CSU games I went to kindergarten with, and that’s pretty special to me.”

————————————————————————————

After every game, and before the season starts, he’s going to get a text message from Brown.

Through her friendship with his parents, Brown always kept tabs on what Jay was doing in life, and she took as much pride in the man he became as any child she’d call her own.

She politely asks, “Can I start from the beginning?”

I still think of my little third-grade Jay. Then I have to realize third-grade Jay is no longer there. I have to treat him like a man and talk to him as a man.Rose Brown

Please do.

“They needed an extra third-grade teacher for class size. You know they’re going to take all the bad children and put them in that new teacher’s class,” she started. “It was the first time they had a Black teacher there, and naturally Jay was excited. I don’t know why they put Jay in there. They gave me about 20 boys, real bad. When I say bad, I mean hyper. Mischievous. Jay stood out. I don’t know if it was because here’s this little Black lady, I better be nice. Maybe they put him in there because I needed a good child.

“He was quiet, but serious. Football was his thing. Every art project was about football. They wanted to play football all the time. He was a happy kid, and I think it had a lot to do with the happiness in his house. He was always cheerful, but not rambunctious. He would let you know he was pleased and would tell you he was happy, but he wasn’t the one to be the loudest one in the group.”

Talking about Brown brings a smile to Jay’s face. She fascinated him then, her being the first teacher he had who looked like him, and she still does. Her energy and her kind words. Her genuine care and devotion when it comes to his wellbeing.

“She was just different than any other teacher I ever had. I just thought she was awesome,” Jay said. “She was no-nonsense, and I related to her really well. I looked up to her. She dealt with boys awesome.

“One of my great memories is when you’re kids and there are disagreements, sometimes kids want to wrestle and push and shove. Well, she’d just box out the corner of the room and let us go at it until we were tired, and she said, ‘have you had enough?’ Everybody loved her because she was a little bit unconventional.”

Those were the days, she said. And she loved her class. She’s also pretty sure she couldn’t handle a group of 20 rambunctious boys in the same manner today.

Schools, she said, are different.

“That’s true. Or I would take them out and say let’s play soccer,” she said. “I don’t think I would teach at this time.”

These days she tracks Jay from afar. She can’t always watch the game, and if it is late, she definitely won’t. She will find out the score, and she watches press conferences and gives him feedback. She sends him messages about how proud she is in the way he conducted himself. Win or lose.

For Jay, that’s the key part. A lot of people are with you when you’re winning. The ones who are really with you never leave.

“As a coach, you get a lot of phone calls when you win, but when you lose, you appreciate those phone calls even more,” he said. “Fred Biletnikoff is a good friend of mine, and when we lose, he’s the first guy to call me. He’ll just start making you laugh … “Sometimes you get the bull, sometimes you get the horns.” You really appreciate when those things aren’t going well, and she always reaches out to me.

“She’s a little bit of a guardian angel for me. She definitely had an influence on me. She’s my favorite teacher I’ve ever had.”

————————————————————————————

Jay’s life community has grown throughout the years, from when he first left home to play for Iowa through each coaching stop. He and Kim have one son, Jayden, but every young man who has played for him has been viewed as family.

A sense of community is what he feels every program needs if it is to thrive. It was the first thing he tried to build in Reno, and he’s doing it again in Fort Collins. It’s the players on the team, the support staff around them and every person who touches the organization at Canvas Stadium and campus wide.

They all have a part, so he treats each as equals. Just as his parents taught him.

“It’s happened over and over. I’ve just been a part of so many of those types of turnarounds, and it’s because you have a sense of community and a sense of belonging,” Jay said. “You’re playing for something bigger than yourself, which is what ultimately turns the tides.

“I think football is a very powerful thing. I tell the kids this: Football is not a coach telling a player what to do and them just doing it, it’s a player and a coach working together. When you recruit and identify a player who has the same mindset you have, now you’ve got something special.”

For the philosophy to work, one needs the ability to connect. Those in his life, who have been part of his life for so long, consider it one of his greatest characteristics. Simmons says Jay is a great football coach. The only thing he does better is connect with people.

Something Hable has known since he was ripping out the knees of his Toughskin jeans in the field next to the church.

“His college nickname at Iowa was Scrap. That was his personality,” Hable said. “He’d scrap for everything, yet his personality and his social nature are the exact opposite. He had more friend groups and still connects with them when he comes back to Madison, guys you’d never think that he’d be connected with. They’re outside of athletics and everything else he’s done.

“I think it’s just his personality that he’s so approachable and available to everyone.”

It’s a gift which has always been valuable in college athletics, where solid programs are built on recruiting. A connection has to be made, and recruits can often tell if they are being offered a pitch or a message from the soul. The gift becomes so much more important these days with the concepts of the transfer portal and Name, Image and Likeness. Not only do coaches have to get them to campus, but they have to be able to keep them there at a time in their life where they may be the most marketable.

Jay can do it now because he’s been doing it forever. This is who he is, and Brown will tell you it is who he has always been. It’s difficult for her to differentiate.

“That’s hard for me to do. I still think of my little third-grade Jay,” she said. “Then I have to realize third-grade Jay is no longer there. I have to treat him like a man and talk to him as a man.”