Money Well Spent With a Greater Return on Investment

Norvell donation aids research on campus and the students doing the work

Mike Brohard

Students come to Colorado State armed with some level of expectation of what their academic journey will entail. Those paths can vary greatly from one department to the next, one person from another due to a myriad of variables.

Most – if not all of the general population at the university – would not expect Jay Norvell to play an instrumental role.

“I think I've told someone that before, just walking around,” graduate student Chris Rocheleau. “I was, ‘oh yeah, I guess I'm going to get EIT (Electrical Impedance Tomography) imaging done in front of the football coach while he's touring our lab.’

“And they're just like: Wait, why?”

When Norvell arrived on campus four years ago, it wasn’t unlike many he’d stepped foot on through his decades as a football coach. Big schools such as Oklahoma, Nebraska, UCLA and Arizona State. There was one very distinct and unique difference about CSU.

As a head coach at his two stops, he and his wife, Kim, have hosted the Grit Run to raise money and awareness for Cystic Fibrosis, which Kim had battled through her entire life. The first time they hosted it at Colorado State, someone noted to him a professor on campus, Dr. Jennifer Mueller, was conducting research around CF.

That was a first for him, to be on a campus doing such research, so he and Kim went to visit Dr. Mueller in her lab. They were impressed and amazed, asking if there was any way they could help.

While the Grit Run has raised nearly $40,000 they have donated to the CF Foundation, the couple have contributed more than $50,000 personally in the past three years to aid Dr. Mueller’s research. Last summer it contributed to her having eight student researchers on campus – led by two graduate students – to further a project. A diverse group from a range of studies on campus, they took an idea which hatched from a class she taught two years ago, advancing the use of EIT to include technology they call the anatomical atlas.

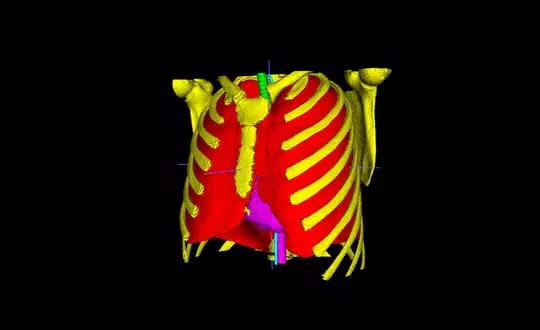

It is still in development, but also currently functional technology that is helping doctors at Children’s Hospital Colorado diagnose and monitor lung problems premature babies. Its ability to create 2D images works well, but the ultimate goal is to have it create 3D images which are clearer and thus more accurate.

“It is called the anatomical atlas because it consists of thousands of simulated EIT scans, and it can be used in several ways to improve our images,” said Dr. Mueller, who holds the Albert C. Yates Chaired Professorship in Mathematics. “We continually want to ensure fidelity, staying true to what is really going on with the patient.

“It was created from CT scans by the students to improve the resolution of the EIT images, which then improves diagnostics.”

A major component of the magic the atlas can provide is improved real-time imaging without any invasive procedure. Some patients, such as the infants Dr. Mueller works with in conjunction with Children’s Hospital Colorado, cannot have multiple CT scans, MRIs or x-rays. EIT uses electrodes which can be attached to the body to provide clear images with no ionizing radiation right at the bedside.

Dr. Mueller and some of her students collect data during visits to the hospital as part of their studies. She and her team have also trained hospital staff to collect EIT data, who have grown in enthusiasm about the results produced.

Dr. Mueller shows slides depicting biological structure, the different organs, even bones, assigned a distinct color. For instance, the lungs are blue, and within the lungs, the shade can alter from dark to light, the darker displaying good air function. The lungs are the primary focus of the research at the hospital, and while those patients are premature babies, the results transfer equally well to CF patients. The lighter shades can alert doctors to areas where air isn’t flowing as well and can point out areas of trapped air. In CF patients, those are problematic since they contribute to low oxygen levels and potential infections.

There is a satellite research project being conducted at Stanford, which is using EIT to improve the placement of endotracheal tubes in newborn infants. The accuracy of the placement will be improved by the anatomical atlas.

Dr. Mueller’s fascination with the project comes not just from what the research has produced, but additionally as an educator.

“It is exciting to me. Especially last summer having the eight undergrads,” she said. “It was exciting to see how much talent was out there. I had to advertise for those positions, and we had so many good applicants, it was hard to narrow it down to eight. It was inspiring to see there are so many undergrads who are generally interested in doing research and have the skills. They really wanted to work and learn. They are a great team.

“The graduate students also learned from it, and they get the experience of teaching the undergrads. They worked with them on a day-to-day basis, organizing the project, teaching them software and anatomy, and answering their questions.”

We go down to Children's Hospital Colorado and we are helping the families that are there and they're a part of this larger support network of all of the patients who have been undergoing the EIT studies, and they get to find a sort of community from that and also there's these people who are working to make things better.Ella Gravante

What their research has produced is as remarkable as the collection of students who have done the work. They came with certain strengths, and in the case of Ella Gravante, will leave with others.

Heading into her senior year, she’s a biochemistry major, minoring in bioinformatics. She came to CSU wanting to do research, but doing medical imaging wasn’t on her to-do list, veering more toward pharmacology. Now, she has an additional set of skills which she is positive will benefit her as she continues on her academic journey.

"The goal of the anatomical atlas is to make it so that we can run the EIT system entirely on the computer. The coding that we did last summer is used to make virtual torsos that we can then use to simulate a variety of different medical conditions. Basically, my job is to translate those torsos into a format that is readable by those simulations. They've really entrusted me with a lot of responsibility on this that I wasn't expecting when I started in the lab last summer,” she said. “But it's been really awesome.

“And I might get a first authorship publication out of the pipeline that I've been working on, which I never would have expected. I'm not a computer scientist by trade. It was just the funding that came in was really like a door opening for me into this opportunity that I've continued on with.”

The coding is the part she didn’t expect she would do -- or even come to appreciate. Her coding is what builds the pipeline she refers to, which will then lead to more accurate algorithms and images, with algorithms needed for each stage of a body’s development – the physiology from an infant to a young adult is much different.

In her eyes, this one project has expanded her growth academically in ways she never expected, and helped create technology which can be useful in so many ways.

“It's really interesting, especially because it's kind of abnormal. Our lab does a lot of pure math applications, but Jennifer is very interesting in the fact that she also really likes doing clinical work,” Gravante said. “So, the pipeline from what you're doing to seeing that you're actually contributing to something is very short, which is very encouraging. We go down to Children's Hospital Colorado and we are helping the families that are there and they're a part of this larger support network of all of the patients who have been undergoing the EIT studies, and they get to find a sort of community from that and also there's these people who are working to make things better.”

Rocheleau came to Colorado State armed with undergraduate and master’s degrees in applied math, the first from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, the second from UMass-Amherst. After eight years in the business sector, he decided to pursue his PhD with the intent of pursuing teaching.

He uses the word serendipity to explain his time at Colorado State, stemming from the fact many of the professors – including Dr. Mueller – have ties to RPI. The word also explains his first class (which was with Dr. Mueller), and the topic, one for which he had a deep personal experience.

While he still has a desire to teach, his work on this particular research project has him hoping he can find dual roles in future endeavors. His time in Fort Collins is not what he envisioned.

“Definitely. In a very good way,” he said. “Yeah, it changed a lot of my career path, my life path. I mostly decided to come back to school because I was working and I did some adjunct teaching on the side and realized I liked one of my jobs way more than the other. And I always say to people, ‘oh, yeah, I know I need to get the doctorate to teach.’ So, I always came in kind of expecting the research would be me eating my vegetables, so to speak.

“But then getting onto this project, doing all this work, seeing the results that are coming out of it ... That's almost shifting my intents. It's making it complicated for me to decide where I'm going to be in a couple of years.”

He and Kyler Howard were the two graduate students who helped oversee the work the undergrads were doing, valuable in their desire to become educators. They were also heavily involved in working with the algorithms and other aspects of the project.

Being able to use his expertise in a way which they all fully believe can have an impact on the world has been more than gratifying, and in essence, was what he was thrilled to find.

“I am an applied mathematician. I came in specifically for the idea I don't want to be doing math for math's sake,” he said. “I want to be doing it to accomplish something. That's always been my approach, but actually having it be something that's not like proof of concept that may someday be used, actually seeing it get out there and be used.

“That's something that even when I worked in engineering, I was always proof of concepts upfront, writing simulations and things of that sort. So, I never actually get to see the systems I was working on in use but now having that very clear pipeline where I can write something up and, if we're super, super good about it, it could possibly be on the system that day.”

I was amazed by how far they’ve come. The things we saw, and the knowledge they’d gained since the first trip was amazing.Kim Norvell

Rocheleau and Howard recently returned from the International Conference on Electrical Bioimpedance and Electrical Impedance Tomography in Mexico where they presented some of their work on the anatomical atlas.

It was daunting, he said, but a conference filled with people who were interested in what they were working on, fielding questions during and after, some asking for further explanation.

Like Gravante, he is on the verge of being published, though with his background he never expected it to be in a medical journal. He is also one of six students on campus who are using some aspects of the research on the anatomical atlas for his PhD thesis, while Gravante will do one for her bachelor’s degree. She also presented her work this year at the CURC showcase.

When Jay and Kim returned to the lab this June, Rocheleau and Howard were on hand to give them a demonstration. Amazed doesn’t cover what they witnessed, understandable considering Rocheleau’s own reaction. As Howard hooked him up with the electrodes in front of the monitor, he put his hand on his heart. He could feel it beating, and though he knows how the atlas improves imaging, it was still remarkable to see what he could feel beating was on the screen in front of him.

“Those kids are so smart. They’ve gotten a lot done since the last time we were there,” Kim said. “I was amazed by how far they’ve come. The things we saw, and the knowledge they’d gained since the first trip was amazing. I told them they were doing things that were going to be a game-changer with the anatomical atlas. You can see the blood flow and the airways … It was so cool. It gives me hope. Every time there’s a major change in technology it benefits young people and that makes me happy.

“The fact we can be a small part of this makes me feel really good about the research. You don’t always know where the money is going, but the fact I can actually see their work makes a huge difference for me, and it does for Jay, too. Part of me is proud that my husband loves me so much he chooses to support this cause because of me.”

Kim was also quick to take note of what was hanging from the ceiling, namely a brain and a heart.

When the lights are turned off in the lab, they glow. Those are a product of using a 3D printer and scans the atlas has created.

They are also a very personal touch. The real things belong to Rocheleau.

“I've always made the joke I've held my heart in my hand,” Rocheleau said. “Even when they were visiting, I did joke there'll be a part of me left in this lab when I leave.”

After their first visit with Dr. Mueller, all Jay wanted to do was help in some small way, emboldened by the fact research was being done on the campus where he worked, research which could someday help someone like his wife.

It never really occurred to him the layered impact of the donation, a very fundamental reason college campuses exist -- to enhance the young minds of those who populate the grounds. When they returned this past June, the connection sparked.

“We give funds to the CF Foundation, but we thought it would be great since the work was being done on campus, it was an additional way to be able to support our own university as well as the students in doing research for cystic fibrosis,” he said. “I thought it was amazing what Dr. Mueller and her students were getting done in a little lab right here on campus.

“I spoke to the Board of Governors and one of the things I said was we believe in the transformational process students go through in college. We’ve committed our careers to that. Coaches are teachers. The first coaches were teachers at Cambridge and Oxford. To be able to support that through Dr. Mueller’s office and her students who are doing this research in the summer is amazing. The progress that was made from last year alone is incredible.”

With classes and her research, Gravante’s free time isn’t in abundance, which makes it rather valuable to her. Like a lot of college students, she does like to take in games, making her way to Canvas Stadium when time permits.

She also has sensed a bit of the rivalry which exists between the academic and athletic forces on campus. Last year on a few Saturday’s, she helped the feeling sway a bit. Sitting with her friends, she said she pointed down at the field at Norvell, explaining it was he and his wife who made her research possible.

A very life-altering detour from the educational experience she expected.

Support Colorado State Athletics: Tickets | Ram Club | Green And Gold Guard